World War II’s ashes were still warm when the Cold War began, and it began in a world that had been fundamentally changed by the former conflict. Warfare would never be the same, especially after the events of Aug. 6 and 9, 1945, but on account of other developments as well. For instance, most major powers were still using biplanes at the outset of WWII, but by its finale the United States, Great Britain, and Germany were deploying jets. Another example is found in the juxtaposition of Germany’s PzKpfw I- and II-centric tank fleets (these were little more than glorified armored tractors with machine guns or 20 mm cannons) at the outset of the war, with its nighttime employment of advanced-infrared equipped PzKpfw Vs at its end. There is also evidence that Germany fielded the world’s first anti-tank guided missile in the closing weeks of the war, and it is regarded as fact that German troops were the first to make use of IR-resistant camouflage.

For a time U.S. planners thought the atomic bomb was the penultimate wartime solution, but a successful atomic test by the Soviets in 1949 invoked the rise of the doctrine of mutually assured destruction, and thereafter it was clear: the A-bomb could only be a weapon of last resort. Furthermore, the Korean War evidenced not only the need for conventional land forces, but also that there would always be a demand for them; actions in British Malaya, the Middle East, and French Indochina drove this point home. Even in the event of a war in Europe, notwithstanding the “go ugly early” strategy about which NATO theorized until the late 1970s, NATO member nations agreed that conventional forces were there to stay and could not be neglected. There to stay, perhaps, but with the nuclear age upon us the direction of their development, especially technologically, was something of a question.

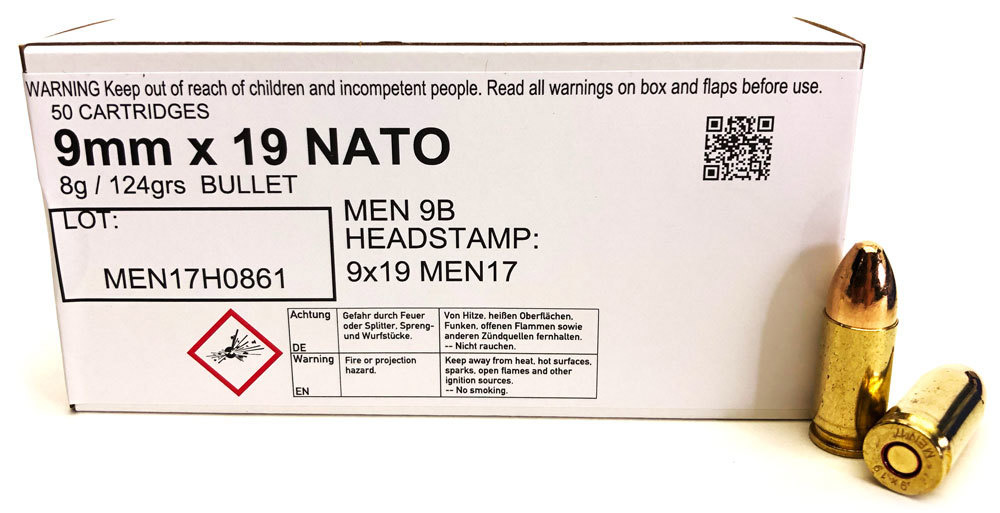

Given opportunities for NATO nations to develop things like laser guided munitions, it’s not difficult to understand how the entire topic of handgun cartridges was relegated to the back burner. And it’s even easier when we handgun enthusiasts face the unfortunate fact that handguns are the least effective, the most poorly understood, and generally the most poorly utilized firearms in combat. However, NATO’s formation did reset Western thinking about defense paradigms, and the new collective mindset eventually brought handgun cartridges into focus, via the decision to standardize equipment and materials across the alliance. Seeing that it would reduce the logistics headache in the event of war, standardization of things like clothing sizes and small arms ammunition made perfect sense. Case in point, aggregation of the 1945 tables of organization and equipment for the infantry forces of all NATO member countries reveals that at least 20 different small arms cartridges would be needed to prepare the alliance for war. While NATO did (and still does) provide a stock number for all of those different cartridges, it really only needed three: an infantry rifle cartridge, a general-purpose machine gun cartridge, and a cartridge for handguns and submachine guns.

There were a number of small arms developments during and immediately following World War II that paved the way to the future. The Sturmgewehr 44 outmoded every other infantry rifle upon the fielding of its first experimental models in late 1942. Britain gave the world its first compact, workable bullpup design complete with a new intermediate cartridge with impressive ballistics. And the United States contributed impressive data on high-velocity .22 caliber rifle cartridges, which it had researched throughout World War II part and parcel to planning for a “next generation” infantry rifle. Accordingly, the West, the paragon of technology and progress, was soon to dazzle the world with its new space-age infantry rifle. Except, it wasn’t. Instead, beset by a “not invented here” complex and a rather testosterone-laden thinking process, the U.S. decided that 7.62×51 should become NATO’s standard rifle cartridge, and no other nation was in a position to disagree. Consequently, the FAL, CETME, and G3, originally designed for intermediate cartridges, were all stretched to accommodate the new 7.62 NATO, while U.S. troops were saddled with the M14 — a glorified M1 Garand with rollers on the bolt and a detachable 20-round magazine. Then, a little more than a decade later, as every non-U.S. NATO army was still trying to equip its soldiers with the first batch of 7.62 rifles, the Americans compelled a shift to 5.56×45.

Considering this multidecade strong-arming of rifle cartridge standardization, it is surprising that the U.S. neither led the charge nor challenged the consensus when other NATO member nations selected 9×19 to become their standard handgun and submachine gun cartridge. Instead, it simply ignored the terms, kept its .45 ACP-chambered 1911 A1s, M3 Grease Guns, and Thompsons, and drove on. Even though U.S. soldiers were generally the most familiar with handguns in all of NATO, the U.S. simply didn’t put much stock in the necessity of handguns or submachine guns, nor in the importance of research and development to eventually replace those currently in service. Choosing rather to focus on things like laser range finders, MIRVs, and BVR-interception technologies, America ignored 9 mm NATO for 30 more years, before finally embracing it in the chambering of its first new general-issue combat handgun since 1911.